The Divine Standard and the Human Condition: a Comprehensive Analysis of the Interplay Between Daniel 9:7 and Matthew 25:45

Daniel 9:7 • Matthew 25:45

Summary: Our analysis explores the profound theological connection between Daniel 9:7 and Matthew 25:45, illuminating the biblical meta-narrative driven by God's immutable righteousness and humanity's fluctuating fidelity. Daniel's confession, "Righteousness belongs to You, O Lord, but to us open shame," establishes a vertical standard of divine integrity in the face of covenantal disobedience. Centuries later, Matthew's apocalyptic pronouncement, "inasmuch as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to Me," projects this standard onto the horizontal plane of the final judgment. We argue that the righteousness attributed to God in Daniel 9 forms the foundational standard, which is ultimately personified in the Son of Man in Matthew 25.

In Daniel 9:7, we see Daniel's prayer during the Babylonian exile, a theological catastrophe for Israel. He defends God's justice by attributing righteousness (Tzedakah) to God, affirming His covenant faithfulness even in meting out judgment. The exile and national disgrace are understood as the "open shame" (Boshet Panim) resulting from Israel's profound unfaithfulness (Ma'al)—a sacrilegious breach of trust with their Suzerain King. Daniel's corporate confession, utilizing the plural "we," highlights the collective guilt of Israel, setting a precedent for collective accountability.

Moving to Matthew 25:45, we encounter Jesus's Olivet Discourse, where the Son of Man, drawing upon Danielic imagery, acts as the ultimate King and Judge. Here, the judgment is pronounced based on the treatment of "the least of these." These individuals, interpreted variously as all suffering humanity, Christian missionaries, or the Jewish remnant, represent the King himself. Crucially, the condemnation issued to the "goats" is for sins of omission—for what they failed to do, revealing a moral blindness that could not discern the King's presence in the vulnerable. This passive rejection mirrors the breach of trust seen in Daniel's "Ma'al."

The dynamic interplay between these texts reveals an escalation from abstract righteousness to personified judgment. The "Righteousness" of God, once an axiom, now resides in Jesus, the King. Daniel's temporal "shame of face" in exile evolves into the "everlasting contempt" mentioned in Daniel 12:2 and concretized as "eternal punishment" in Matthew 25:46 for those who remain indifferent. Both narratives underscore that neglecting God's representatives—the prophets in Daniel, or the "least of these My brothers" in Matthew—leads to profound condemnation. Our analysis warns that neutrality is an illusion; systemic inaction or unfaithfulness, whether active treason or passive omission, inevitably leads to "open shame" and ultimate separation from the King's presence. True righteousness, as seen in the "sheep," begins with Daniel's humble confession and is demonstrated by active love that recognizes Christ in the marginalized.

1. Introduction: The Dialectic of Righteousness and Judgment

The biblical meta-narrative is frequently propelled by the tension between the immutable character of God and the fluctuating fidelity of His people. This tension finds its most articulate expression in the interplay between the prophetic confessions of the Old Testament and the eschatological pronouncements of the New Testament. Specifically, Daniel 9:7 and Matthew 25:45 stand as monumental pillars at opposite ends of the redemptive-historical spectrum, yet they share a profound theological DNA. Daniel 9:7, situated in the context of the Babylonian exile, articulates a vertical theodicy: "Righteousness belongs to You, O Lord, but to us open shame". Centuries later, Matthew 25:45 projects this vertical standard onto a horizontal plane in the final judgment of the nations, where the King declares, "Assuredly, I say to you, inasmuch as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to Me".

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of these two texts, exploring their philological roots, historical contexts, and theological interconnections. It argues that the "righteousness" attributed to God in Daniel 9 is the foundational standard that is eventually personified in the Son of Man in Matthew 25. Furthermore, the "open shame" confessed by Daniel finds its ultimate eschatological resolution—or concretization—in the "everlasting contempt" and "eternal punishment" awaiting those who fail to align with the divine character. By examining the nuances of Hebrew and Greek terminology, the sociology of shame, and the varying hermeneutical approaches to the "least of these," this analysis demonstrates how the prophetic confession of corporate guilt in Daniel informs the apocalyptic judgment of corporate omission in Matthew.

2. The Covenantal Context of Daniel 9:7

To understand the weight of Daniel 9:7, one must first appreciate the crushing historical and theological crisis that precipitated it. The year is approximately 539 B.C., the first year of Darius the Mede. The Babylonians, the instrument of God's wrath, have fallen to the Medo-Persians, yet the desolation of Jerusalem remains. Daniel, an elderly statesman and prophet, turns to the scrolls of Jeremiah, discerning that the number of years for the desolation of Jerusalem—seventy—was nearing completion.

2.1 The Crisis of the Exile and the Prophetic Response

The exile was not merely a geopolitical defeat; it was a theological catastrophe. For the Israelite, the destruction of the Temple and the loss of the Land raised terrifying questions about the power and faithfulness of Yahweh. Had the gods of Babylon defeated the God of Israel? Daniel’s prayer in chapter 9 is a theodicy—a defense of God’s justice. He preempts any accusation against God by declaring that the catastrophe is the result of Israel’s covenant violation, not God’s impotence or unfaithfulness.

The prayer is characterized by "focused attention" (setting his face), accompanied by fasting, sackcloth, and ashes—traditional rites of mourning and humiliation. This is not the prayer of a detached observer but of a participant in the national tragedy. Daniel, though personally righteous and blameless in the narrative (having survived the lion's den and navigated pagan courts without compromise), identifies completely with his people’s sin. He uses the plural "we" repeatedly: "we have sinned," "we have rebelled," "we have not listened".

2.2 Exegetical Analysis of Daniel 9:7

The verse in question reads: "To You, O Lord, belongs righteousness, but to us open shame, as it is this day—to the men of Judah, to the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and all Israel, those near and those far off in all the countries to which You have driven them, because of the unfaithfulness which they have committed against You".

2.2.1 The Attribution of Righteousness (Tzedakah)

The Hebrew Lekha Adonai HaTzedakah ("To You, Lord, the righteousness") is emphatic. Tzedakah in this context is not merely an attribute of moral purity but a relational concept denoting adherence to a standard or norm. It signifies God’s covenant faithfulness. Paradoxically, God’s righteousness is demonstrated in His judgment of Israel. Because He is righteous, He must fulfill the covenant curses explicitly outlined in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28 for disobedience. If God had not punished Israel for their persistent rebellion, He would have been unrighteous—unfaithful to His own word. Thus, Daniel asserts that the exile is proof of God’s integrity, not His failure.

2.2.2 The Reality of "Open Shame" (Boshet Panim)

In stark contrast stands the condition of the people: u-lanu boshet ha-panim ("and to us, shame of the face"). The term boshet refers to the objective state of disgrace and public humiliation. In an honor-shame culture, "face" represents one's social standing and dignity. To have "shame of face" means to be unable to lift one's head, to be exposed as a failure before the watching world.

This shame is described as "open" or "as it is this day," referring to the tangible reality of their dispersion and subjugation. It is a visible sign of their inward corruption. The shame is not just a feeling of embarrassment but a forensic declaration of their status as covenant-breakers.

2.2.3 The Cause: Unfaithfulness (Ma'al)

The root cause of this shame is identified as ma'al, translated as "unfaithfulness," "treachery," or "trespass". This term is technically precise in priestly literature (Leviticus 5:15, Numbers 5:6). It denotes a sacrilege or a violation of holiness, often involving the misappropriation of property dedicated to God or a breach of trust in a covenant relationship. By using ma'al, Daniel diagnoses Israel’s sin as "high treason" against their Suzerain King. It implies that the exile is not a result of a minor moral lapse but of a systemic, structural betrayal of the divine relationship.

| Hebrew Term | Root Meaning | Theological Implication in Daniel 9:7 |

| Tzedakah | Straightness, standard, justice |

God's adherence to Covenant sanctions; His justice in exiling Israel. |

| Boshet Panim | Shame of face, confusion |

The objective sociological and theological disgrace of the Exile. |

| Ma'al | Treachery, covert act, sacrilege |

The specific nature of sin as a violation of Covenant trust. |

2.3 Corporate Personality and Collective Guilt

Daniel’s prayer relies heavily on the ancient Near Eastern and biblical concept of "corporate personality." In this worldview, the individual is inextricably bound to the community (clan, tribe, nation). The actions of the "fathers," "kings," and "princes" implicate the entire populace.

This concept is crucial for understanding the interplay with Matthew 25. Daniel does not pray as an innocent individual seeking personal exemption; he prays as a representative of the guilty group. He acknowledges that the shame belongs to "all Israel, near and far". This collective responsibility establishes the precedent for the "judgment of the nations" in Matthew, where entire groups (ethne) are assessed based on their collective behavior.

3. The Apocalyptic Landscape of Matthew 25:45

Moving from the historical exile of Daniel to the eschatological horizon of Matthew, we encounter the "Olivet Discourse." Jesus, sitting on the Mount of Olives (a location rich with Zechariah’s messianic prophecy), outlines the future of the cosmos, the destruction of the Temple, and the end of the age. The discourse culminates in the scene of the Final Judgment (Matthew 25:31-46), often called the Parable of the Sheep and Goats, though it lacks the typical narrative structure of a parable and is more of a prophetic revelation.

3.1 The Son of Man: Danielic Imagery Reimagined

Matthew 25:31 opens with, "When the Son of Man comes in His glory, and all the holy angels with Him, then He will sit on the throne of His glory". This is a direct invocation of Daniel 7:13-14, where "one like a son of man" comes with the clouds of heaven.

-

In Daniel 7: The Son of Man is a figure who approaches the Ancient of Days (God) to receive a kingdom. He is vindicated against the "beasts" (earthly empires) that oppressed the saints.

-

In Matthew 25: The Son of Man is the King and Judge. He has received the kingdom and now exercises the prerogative of judgment that belongs to God.

This identification is vital. The "Righteousness" that Daniel 9:7 says "belongs to Yahweh" is now administered by Jesus, the Son of Man. He is the standard. The judgment is no longer mediated through historical events like the Babylonian exile but is delivered directly "face to face" by the King.

3.2 Exegetical Analysis of Matthew 25:45

The verse reads: "Then He will answer them, saying, 'Assuredly, I say to you, inasmuch as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to Me'".

3.2.1 The "Least of These" (Elachistos)

The Greek term elachistōn is the superlative of mikros (small), meaning the smallest, least significant, or lowest in rank. In the context of the passage, these "least" are defined by their suffering: hungry, thirsty, strangers, naked, sick, and imprisoned.

The critical interpretive battleground lies in the identity of these individuals. Who are the "least"?

-

The Universal Poor (Social Justice View): This view argues that Jesus identifies with all suffering humanity. The judgment is based on universal humanitarian ethics. Support is found in the broad wisdom tradition of caring for the poor (Prov 19:17) and the lack of explicit restriction in the text to "believers".

-

The Missionaries/Disciples (Ecclesial View): This view posits that "brothers" (adelphoi) in Matthew almost always refers to disciples (Matt 12:48-50, 28:10). The "least" are the itinerant Christian missionaries who are hungry and imprisoned because of their mission. The nations are judged on whether they received the King's messengers.

-

The Jewish Remnant (Dispensational View): This view interprets "my brethren" as the Jewish people specifically, particularly during the "Great Tribulation" (Jacob's Trouble). The "nations" (Gentiles) are judged based on their treatment of persecuted Israel, fulfilling the Abrahamic promise: "I will bless those who bless you, and curse him who curses you" (Gen 12:3).

3.2.2 The Sin of Omission

The condemnation in verse 45 is notable for what it does not cite. The "goats" are not accused of idolatry, murder, or theft—the classic sins of commission. They are condemned for what they did not do. "Inasmuch as you did not do it...". This mirrors the concept of ma'al in Daniel: a breach of trust. In the Kingdom economy, neutrality is impossible. Failure to act in the face of need is interpreted as active rejection of the King.

3.2.3 The Surprise of the Accused

"Lord, when did we see You...?" (Matt 25:44). The "goats" are stunned. They imply that had they known it was the King, they certainly would have helped. Their blindness is their indictment. They judged by appearances (seeing only a beggar), whereas the King judges by reality (seeing His own image/presence). This connects back to Daniel 9:7 where the people’s sin led to "confusion of face"—a moral disorientation where they could no longer discern the requirements of God.

4. The Interplay: Synthesizing Daniel and Matthew

Having analyzed the texts individually, we now explore their dynamic interplay. The theological movement from Daniel 9 to Matthew 25 is one of escalation and concretization.

4.1 From Abstract Righteousness to Personified Judgment

In Daniel 9:7, "Righteousness belongs to You" acts as a theological axiom. It is the premise of Daniel’s prayer. In Matthew 25, this righteousness takes on flesh. The King is the Righteous One. The standard is no longer just the Law of Moses (as cited in Dan 9:11), but the person of Jesus.

-

Daniel's Standard: The Covenant Law (Deut 28 / Lev 26). Breach = Exile.

-

Matthew's Standard: The King’s Presence (in the Least). Breach = Eternal Fire.

The "righteousness" of the sheep in Matthew 25:46 ("the righteous into eternal life") is derived from their alignment with the King’s character. Just as Daniel acknowledged God’s righteousness in judging sin, the sheep demonstrate righteousness by loving what God loves.

4.2 From "Shame of Face" to "Everlasting Contempt"

The "open shame" (boshet panim) of Daniel 9:7 is a temporal judgment—the exile. However, Daniel 12:2 expands this trajectory into the eternal realm: "And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt".

Matthew 25:46 is the direct fulfillment of Daniel 12:2. The "everlasting contempt" (deraon olam) corresponds to the "eternal punishment" (kolasin aionion) of the goats.

-

Daniel 9:7: Shame is historical and national (Exile).

-

Daniel 12:2: Shame is eschatological and individual (Resurrection).

-

Matthew 25:46: Shame is final and retributive (Hell).

The "shame of face" in Daniel 9 implies a loss of access to God’s presence. The "eternal punishment" in Matthew 25 is the ultimate realization of this loss—being cast "away" from the King into the outer darkness.

| Text | Nature of Shame/Punishment | Duration | Context |

| Daniel 9:7 | "Shame of face" (Boshet Panim) | Temporal / Historical | Babylonian Exile; National disgrace. |

| Daniel 12:2 | "Everlasting Contempt" (Deraon Olam) | Eternal | Resurrection of the dead. |

| Matthew 25:46 | "Eternal Punishment" (Kolasin Aionion) | Eternal | Final Judgment of Nations. |

4.3 The "Brothers" and the "Prophets"

In Daniel 9:6, Daniel confesses, "We have not listened to Your servants the prophets." These prophets were the representatives of God sent to warn the people. In Matthew 25, the "least of these My brothers" function in a similar prophetic role. Whether viewed as missionaries or simply the marginalized, they are the representatives of the King.

Rejection of the prophets led to the "shame" of the exile (Dan 9). Rejection of the "brothers" leads to the "punishment" of eternal fire (Matt 25). The principle of agency (Shaliach in Hebrew) undergirds both: "He who receives you receives Me" (Matt 10:40). The treatment of the representative is the treatment of the Sender.

4.4 Corporate Solidarity in Judgment

Daniel 9 establishes the validity of corporate guilt ("To us... to our kings... to all Israel"). Matthew 25 maintains this corporate dimension by gathering "all the nations" (panta ta ethne). While modern individualism often recoils at collective judgment, both texts presume that societies have a moral personality.

However, Matthew introduces a differentiation within the corporate body. The nations are gathered, but the King separates them "one from another" (Matt 25:32). This suggests that while nations are judged, the ultimate destiny is determined by the specific alignment of the "sheep" vs. the "goats." The corporate context of Daniel 9 (where the righteous Daniel suffers with the wicked nation) gives way to the separating judgment of Matthew 25 (where the righteous are finally distinguished from the wicked).

5. Scholarly Perspectives on the "Least of These"

Because the identification of the "least" dictates the application of Matthew 25:45, a detailed examination of the scholarly landscape is necessary to fully unpack the interplay.

5.1 The Universal/Social Justice Interpretation

This view, dominant in mainline Protestantism and Catholic social teaching, argues that the "least" are the poor, regardless of faith.

-

Arguments: It aligns with the prophetic tradition (Amos, Isaiah) that equates righteousness with care for the poor. It fits the "surprise" element best (why would the righteous be surprised they helped Jesus if they were helping known Christian missionaries?).

-

Relevance to Daniel: It connects to the Ma'al of Daniel 9 as a failure of social ethics. The exile happened because Israel neglected justice (Jeremiah 22:3). Thus, the "shame" of Daniel 9 is the result of systemic social failure.

5.2 The Ecclesial/Missionary Interpretation

Supported by scholars like Craig Keener and evangelical theologians, this view limits "brothers" to believers.

-

Arguments: The Greek adelphoi in Matthew consistently refers to disciples. The context of Matthew 10 ("he who gives a cup of cold water to a disciple") parallels Matthew 25 perfectly. The judgment is about how the world treats the Church.

-

Relevance to Daniel: This parallels the rejection of the prophets in Daniel 9. The world is judged by how it treats God's messengers. The "shame" of the nations is their rejection of the Gospel message carried by the "least".

5.3 The Dispensational/Jewish Interpretation

This view, common in futurist eschatology, identifies the "brethren" as the 144,000 Jewish witnesses or the Jewish remnant during the Tribulation.

-

Arguments: The context is the Olivet Discourse regarding the end of the age and the future of Israel. The "nations" (Gentiles) are judged on their anti-Semitism or support for Israel during the time of "Jacob's Trouble."

-

Relevance to Daniel: This view creates the tightest link to Daniel 9. The "70th Week" of Daniel 9:24-27 is the Tribulation period. Matthew 25 is the judgment at the end of that 70th week. The "shame" of Daniel 9:7 (the exile/dispersion) is finally resolved when the nations are judged for how they treated the dispersed Jews (the "brethren").

| Interpretation | Identity of "Least" | Connection to Daniel 9 |

| Social Justice | All poor/marginalized | Ma'al as social injustice; failure of ethics causes shame. |

| Missionary | Christian disciples | Rejection of prophets (Dan 9:6) parallels rejection of missionaries. |

| Jewish/Dispensational | Jewish Remnant | The end of the "70 Weeks"; judgment of nations for treating dispersed Israel (Dan 9:7). |

6. Broader Theological Implications

6.1 Structural Injustice and the Silence of the Good

Both texts confront the reality of passive complicity. In Daniel 9, the entire nation is guilty, even those who perhaps did not personally worship idols but allowed the system to rot. In Matthew 25, the goats are condemned for doing nothing. This indicts "structural injustice"—systems that render the poor invisible. The "shame" of Daniel 9 is the inevitable collapse of a society built on such structural "unfaithfulness" (ma'al). The warning for contemporary societies is that "open shame" is the destiny of any civilization that ignores the "least".

6.2 The Anatomy of Confession

Daniel 9:7 teaches the necessity of "we" prayers. In an individualistic age, the concept of repenting for national or corporate sins is foreign. Yet, the interplay suggests that restoration (the "everlasting righteousness" of Dan 9:24) only begins with the honest admission of corporate shame ("To us belongs shame of face"). There is no salvation in Matthew 25 for those who claim ignorance; the only safety lies in the prior alignment with the King’s character, which begins with the humility of Daniel’s confession.

6.3 Eschatological Reversal

Both texts operate on the principle of reversal.

-

In Daniel: The mighty Babylonian empire falls; the shamed exiles are restored (eventually).

-

In Matthew: The "goats" (often the wealthy, powerful nations) are cast out; the "least" (the hungry, naked) are revealed as the VIPs of the Kingdom. This "transvaluation of values" is the hallmark of apocalyptic literature. What appears to be "shame" in the eyes of the world (suffering, poverty, exile) is often the prelude to glory, while worldly "glory" (power, indifference) leads to "everlasting contempt".

7. Conclusion

The interplay between Daniel 9:7 and Matthew 25:45 is a journey from the depths of national humiliation to the pinnacle of cosmic judgment. Daniel 9:7 establishes the premise: God is righteous, and humanity, in its treasonous unfaithfulness (ma'al), bears the "open shame" of its rebellion. This shame is historically visible in the exile and the scattering of the people.

Matthew 25:45 brings this drama to its ultimate resolution. The Righteousness of God is no longer a distant attribute but the presiding King, the Son of Man. The test of faithfulness is no longer merely ritual adherence but the recognition of the King in the "least of these." The "shame of face" that Daniel confessed becomes the "everlasting contempt" for those who persist in blindness and neglect. Conversely, for those who embrace the "least"—whether they be the poor, the missionary, or the persecuted Jew—the shame is transformed into the "eternal life" of the Kingdom.

Ultimately, these texts warn that neutrality is an illusion. One either aligns with the Righteousness of God through active love and confession, or one drifts into the "open shame" of indifference. The cry of Daniel—"To us belongs shame"—is the necessary starting point for anyone who wishes to hear the King say, "Come, you blessed of My Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you" (Matt 25:34).

8. Tables and Data Synthesis

Table 1: Comparative Philology of Key Terms

| Feature | Daniel 9:7 (Hebrew) | Matthew 25:45 (Greek) | Thematic Link |

| Divine Attribute | Tzedakah (Righteousness) | Dikaios (Righteous - v.46) | God's character is the standard for both historical discipline and final judgment. |

| Human Condition | Boshet Panim (Shame of Face) | Kolasin Aionion (Eternal Punishment) | The objective disgrace of sin evolves from temporal exile to eternal separation. |

| The Sin | Ma'al (Unfaithfulness/Treachery) | Ouk Epoiēsate (You did not do it) | Both denote a breach of covenant trust; one active (treachery), one passive (omission). |

| The Victim | "Prophets" (v.6), "Israel" (v.7) | "Least of these," "Brothers" | Rejection of God's representatives is the basis for condemnation in both eras. |

Table 2: The Trajectory of Judgment

| Stage | Textual Basis | Nature of Judgment | Outcome |

| 1. Historical | Daniel 9:7 | Corporate / National | Exile, Dispersion, "Open Shame." |

| 2. Prophetic | Daniel 12:2 | Individual / Eschatological | Resurrection to "Everlasting Contempt." |

| 3. Final | Matthew 25:31-46 | Universal / Trans-historical | Separation of Sheep/Goats; Eternal Fire vs. Life. |

This analysis confirms that Daniel 9:7 and Matthew 25:45 are not isolated fragments but interconnected keystones in the biblical theology of justice. They articulate a unified warning: The Righteous God sees the hidden treachery of the human heart, and the only escape from the shame of judgment is a life poured out for the "least of these," in whom the King Himself resides.

What do you think?

What do you think about "The Divine Standard and the Human Condition: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Interplay between Daniel 9:7 and Matthew 25:45"?

Related Content

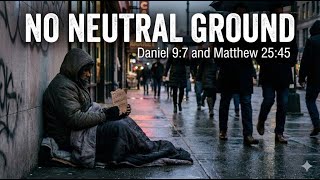

No Neutral Ground

Beyond Playing It Safe: Our Faith Demands Action

Daniel 9:7 • Matthew 25:45

Edmund Burke famously observed that the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing, a truth that stands as a haunting ...

The Enduring Standard: from National Shame to Eternal Judgment and Compassionate Life

Daniel 9:7 • Matthew 25:45

The grand narrative of scripture is driven by the dynamic tension between the unchanging perfection of God and the inconsistent obedience of humanity....

Read in Context

Click to see verses in their full context.

Song (Other Languages)